Throughout history, the quest to automate complex calculations has led humankind on an extraordinary journey—one that culminated in the invention of the world’s first computer. But unlike modern inventions, the origin of computing is layered in a fascinating web of conceptual breakthroughs, mechanical prototypes, and visionary designs. Pinpointing the person who invented and designed the world’s first computer requires understanding the intersection of mathematics, engineering, and a substantial amount of visionary imagination during a period long before transistors or digital logic ever existed.

The honor of conceptualizing and designing the first general-purpose computer is most often attributed to the 19th-century mathematician and inventor Charles Babbage. Known famously as the “Father of the Computer,” Babbage never saw his full invention built during his lifetime, but his designs laid the critical groundwork for what we consider the modern computer today.

The Seeds of Invention: Pre-Babbage Innovations

Before diving into Babbage’s remarkable contributions, it is important to acknowledge earlier mechanical devices that aimed to aid or automate calculations. Long before the 1800s, civilizations had constructed tools like the abacus for arithmetic operations. During the 17th century, innovations such as:

- Blaise Pascal’s Pascaline – A mechanical calculator invented in 1642 that could perform addition and subtraction.

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s Step Reckoner – A more advanced device capable of multiplication and division.

While these machines were groundbreaking, they were limited to specific predefined calculations and couldn’t be programmed to perform a sequence of operations based on logic—a defining trait of modern computers.

Charles Babbage and the Analytical Engine

Charles Babbage (1791–1871), a British polymath, became obsessed with the inefficiencies and errors riddling human computation, such as those found in mathematical tables used for navigation and engineering. He envisioned creating a mechanical device that would resolve these problems.

His earliest prototype, the Differential Engine, was conceived in the 1820s and designed to calculate and tabulate polynomial functions automatically using finite differences. It was a major mechanical undertaking involving thousands of moving parts and gears. Despite initial funding from the British government, Babbage never completed the machine due to technical and financial difficulties.

However, it was what came next that truly earned him his reputation in the annals of computing history: the Analytical Engine.

The Analytical Engine: A Real Computer Before Its Time

Designed in 1837, the Analytical Engine was radically ahead of its time. If it had been completed, it would have comprised the fundamental components we associate with modern computing:

- The “Mill”: An arithmetic logic unit to process calculations.

- The “Store”: Memory that could hold up to 1,000 numbers of 50 decimal digits.

- Input/Output Mechanisms: Punched cards, inspired by the Jacquard loom, to input commands and output results.

- A Control Unit: To interpret instructions and loop through conditional operations.

These components form the conceptual basis for what is now known as the Von Neumann architecture—a model still used in most modern computers. What’s astonishing is that Babbage developed this model using mechanical means, far before electricity came into wide application.

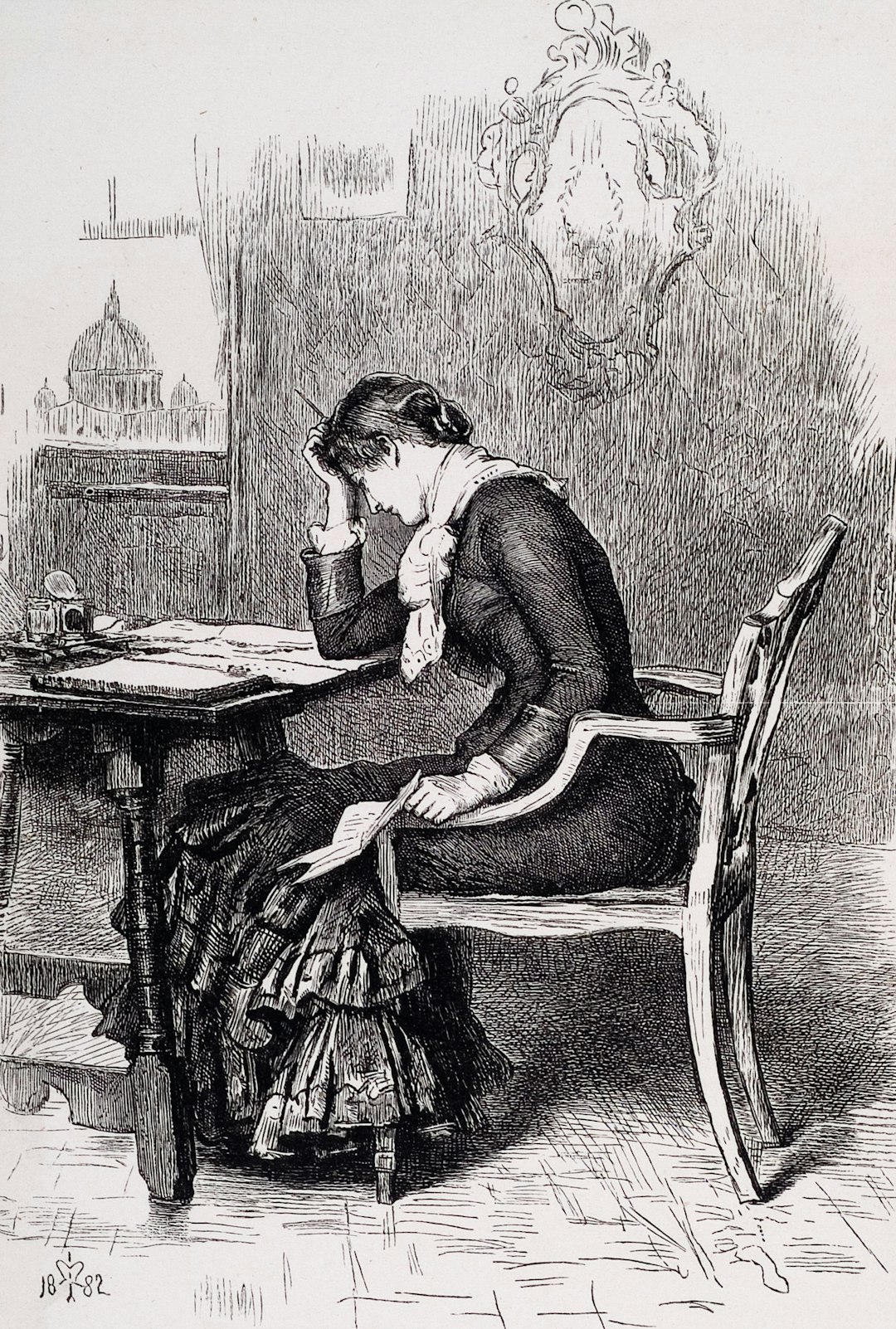

A Visionary Colleague: Ada Lovelace

No discussion about the birth of computing would be complete without highlighting Ada Lovelace, daughter of the poet Lord Byron and a brilliant mathematician in her own right. Lovelace collaborated closely with Babbage and is often credited with writing the first recognized computer algorithm.

While translating an Italian engineer’s notes on Babbage’s Analytical Engine in 1842, she added extensive annotations—so extensive that her notes tripled the length of the original work. In one of these annotations, she described a method for computing Bernoulli numbers using the machine’s capabilities. Her work revealed a deep understanding of the machine’s potential for general-purpose computing, not just number crunching.

For this reason, Ada Lovelace is celebrated today as the world’s first computer programmer.

Why Babbage’s Computer Was Never Built

Though visionary, the technology and manufacturing capabilities of the 19th century were not advanced enough to realize the device Babbage had imagined. His designs demanded extreme mechanical precision and complex parts, which the tools of his era could not produce reliably or cost-effectively.

Nonetheless, meticulous documentation of Babbage’s plans survived. In fact, in 1991—over 150 years after it was designed—the London Science Museum successfully built a working model of the Differential Engine No. 2 based entirely on Babbage’s blueprints. It operated exactly as intended, confirming the genius of his designs.

Other Pioneers Worth Mentioning

While Babbage and Lovelace laid the foundational concepts of computing, other individuals also made significant contributions to what eventually became the modern computer:

- Alan Turing: Considered the father of theoretical computer science; developed the concept of the Turing machine in the 1930s.

- Konrad Zuse: In 1941, built the Z3, considered the first programmable, fully automatic digital computer.

- John Atanasoff and Clifford Berry: Developed the Atanasoff-Berry Computer (ABC), which introduced binary processing in the late 1930s.

- John von Neumann: Formalized the stored-program architecture still used in modern computers.

However, these advances came in the 20th century and built upon the conceptual foundations laid by Babbage and others decades earlier.

The Legacy of Babbage’s Work

Though he never saw his Analytical Engine completed during his lifetime, Babbage’s conceptual leap from mere calculation devices to a programmable machine was the defining moment in computer history. His insistence on separating data from instructions, use of memory for temporary storage, and logical decision-making in the machine became cornerstones of what we now take for granted in computing.

Today, both Babbage and Lovelace stand as lasting symbols of innovation and intellectual courage. In a time when steam was the pinnacle of technology, they imagined machines that could think, remember, and iterate through steps without human intervention. Their vision remains imprinted on every digital device we use today.

Conclusion

The question of who invented and designed the world’s first computer is not just about the construction of hardware—it is about ideas, foresight, and revolutionary design. In that sense, Charles Babbage undeniably brought the vision of the modern computer into being well before his time. Together with Ada Lovelace, they formed a partnership that anticipated nearly every hallmark of computing we recognize in the digital age.

Although many others contributed to the field in the following century—and built actual working machines—it all began in the dusty pages of Babbage’s notebooks and the mathematical annotations of a woman who saw far deeper into the machine’s potential than anyone else of her time.